Do you listen to music? Of course, we all do.

Then, you should have come across ‘Pitchfork’. Considered the “trusted voice in the music”, the publisher has influenced millions of music fans and helped hundreds of independent music artists.

Along the way, the publisher has also grown its advertising revenue and became an intrinsic part of the Conde Nast group.

Table of Contents

Why Pitchfork?

When we hear Pitchfork, we often tend to see the grand events and impressive revenue numbers. As always, there’s more than what meets the eye.

Pitchfork was started by a high school kid (just after graduating), Ryan Schreiber with no prior experience in writing and online publishing.

This means you won’t see any staggering traffic or revenue in the beginning. The hockey stick graph of Pitchfork took time and a clean strategy to hit the apex.

When Pitchfork went live, the year was 1995. Remember, there were only around 23k websites back in the day and it was hard to sustain even for the legacy publishers like The Guardian, FT, etc.

So, it’s quite easy to predict that the publisher would have struggled a lot and implemented tons of successful strategies. Let’s dive in.

How it all started?

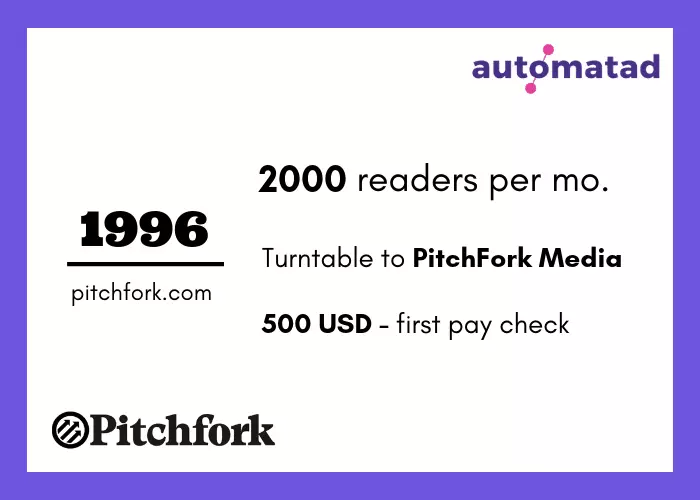

Young Schreiber (19), who was just out of high school started a webzine named Turntable.

In the early stages, he posted a few reviews every month, worked on his tech skills, created everything on his own, and interviewed every band he could. Schreiber was a telemarketer and record store clerk by night, Pitchfork editor by day.

And, the site was attracting roughly 2000 readers a month, as per Ryan till ‘99. It took him 2 years to earn the first paycheck (Src).

Where are they today?

Now, Pitchfork is garnering over 43 million page views every month from its 7 million unique millennial readers. From a one-person publisher, it has grown to employ 50 full-time staffers and a network of freelance journalists (Src).

In addition, they run a couple of music festivals and credit the best indie music and artists with the “Pitchfork Awards”

Revenue, readership, authenticity, reach, they’ve grown in every aspect you could think of. Considering the humble beginning and inexperienced founder, it is apparent that the publisher has a lot to teach us.

Let’s see the strategies and decisions that helped Pitchfork to grow into “the most trusted voice in music”.

Becoming the Pitchfork

Patching Up The Void

1996

We’re not sure about you, but when we came to know that a 19-year-old started a website criticizing music back in 1995, we went ‘what?’. Because we knew how legacy print publications struggled to hold their presence online.

From the Guardian to Financial Times, teams were working round the clock to figure out the internet. So, how does Pitchfork happen?

Well, you should thank the traditional magazines and of course, the Internet.

In an interview with Mediabistro, Ryan revealed that he’s quite used to the Internet by the time Pitchfork launched. In 1996, the music industry in the UK was vibrant, thanks to the success of Britpop.

But in the US, there wasn’t anything. Traditional music magazines still followed the monthly/quarterly routines to release titles and no one seems to capitalize on the internet. Ryan believed that there is some gap to talk about independent music.

“There were not a lot of music publications or anything like that online, but especially for independent music it was really just a blank slate. And I had always been interested in publishing and music writing and criticism.”

– Src.

He then created a webpage called Turntable and the rest is history.

Note: NME.com, a British music journalism website launched in 1996 took advantage of the void. But it isn’t the only factor that helped online music journalism. The legacy titles stuck to the periodic print schedules and operations long enough to let the new online websites thrive.

Pitchfork Style

It’s worth mentioning the style and the tone of the website. Though it has been criticized by many, the publisher never changed its tone. And, if you’re wondering where it all started, look no more than the founder himself.

He was the editor-in-chief of Pitchfork from the start to 2015. He was replaced by Spin Editor-in-chief Puja Patel after the M&A with Conde Nast.

He read a ton of music magazines and DIY fanzines while running the website. And, he knows what the people want to hear about and what is missing in the print titles. From there, he would explore indie music and pitch every artist he could to get an interview.

“I was calling up labels out of the blue like, ‘Hi I have this music magazine on the Internet and people were like, ‘On the what?’”

Improved Business Model

When you look at it first, you might think the story is too good to believe. How can someone with no prior experience in journalism run a site about music journalism?

He didn’t have first-hand experience. But he saw his friends printing fanzines with scrappy content and designs.

He also noticed how expensive was it to print and distribute them. So, he thought ‘why can’t we do it online?’.

There’s the worldwide web and people are getting used to reading online (mainly because of the online news websites). His passion for music and knack for business was enough to propel the idea.

Unique Rating System

Yet another thing to notice is the rating system of the publisher. Unlike many, the publisher has a precise rating system where the reviewer has to rate the album or song from 0.0 to 10.0.

If you think it is weird, you’re not alone. It has been widely mocked online and in 2007, The Onion published a story deriding the rating system of the publisher. The title of the piece is enough to show you the context – “Pitchfork Gives Music 6.8”.

The ratings helped the publisher by,

a. Standing out from the crowd – Readers were used to five stars or x out of 10 ratings of the traditional magazines. The decimal numbers were enough to let readers discern Pitchfork from the rest.

b. Precision – The precise rating numbers indirectly push the reviewer to break down the album or song or artists to the deepest level possible and help them to zoom in on infinitesimal music notes. And, many fans loved it.

Besides, the publisher sprinkled sarcasm and criticized the albums with 0.0 ratings (more on this later).

Rechristening of Turntable

During the same year, Turntable, a webzine became Pitchfork Media, a media company, as another site claimed rights to the original name. This is the point where the publisher realized it could a bigger media company rather than a local webzine.

First paycheck

1997

The next step was clear for the publisher. It needs to get sponsors and advertisers to sustain and thrive. For almost 2 years, the site was bleeding the cash and supported solely by the founder.

What happened next?

Ryan started calling labels and local businesses to see if they’re interested to run ads on the site. It was an experiment to see if he could scale the site and get some revenue. Eventually, he got some local businesses paying him to run ads.

Specifically, the first paycheck was from the online record store, “Insound” that wanted to advertise on Pitchfork. The pay was 500 USD, this was a turning point for Pitchfork and it launched itself into the advertising industry.

What’s interesting about the deal?

Pitchfork Media isn’t attracting thousands of readers every day. There were a few thousand in a month. However, the site attracted targeted local readers and made them stay longer.

Viral content

2000

Online journalism wasn’t exuberant in the early days. Though you could see a number of portals offering reviews and ratings, there’s not much difference. In the midst of lumbering online sites, Pitchfork went off the track. For instance, the publisher’s infamous review of Jet’s second album Shine On featured a money video (only the video) and it spread across the social networks (communities).

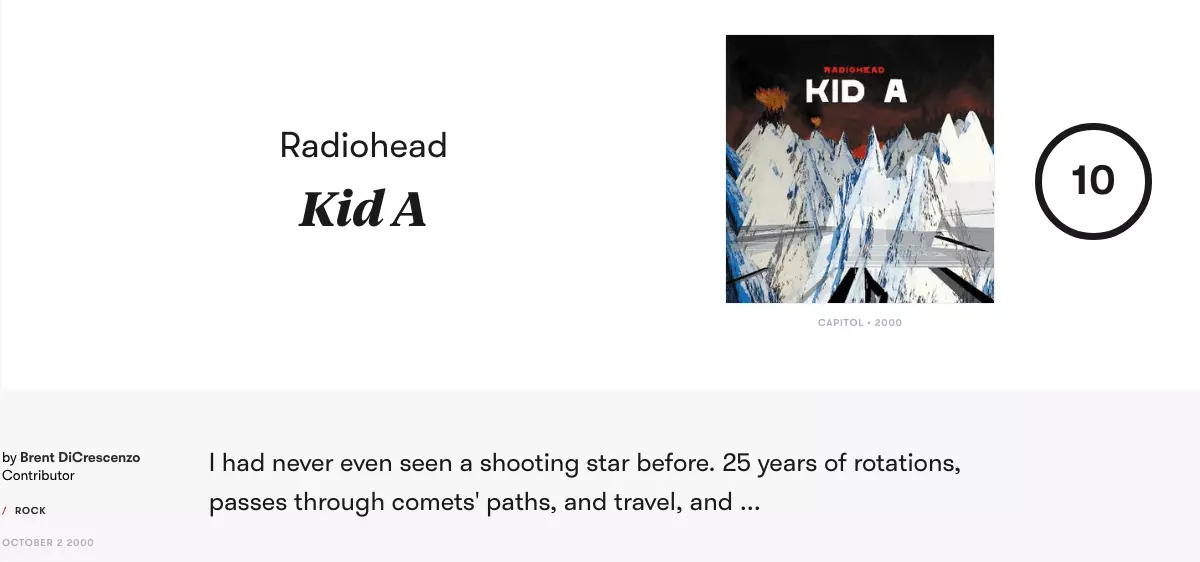

Also, the review of Radiohead’s Kid A broke the Internet because of the shareable feel, funky style, and viral-friendly content.

Real traction

*Radiohead’s Kid A review attracts thousands of readers every month to this day

Every niche publisher needs a viral piece to skyrocket their traffic and reach. Fortunately, Pitchfork’s notorious review of Radiohead’s “Kid A” was a great hit. It attracted an unbelievable amount of readers who now became regular visitors of Pitchfork.

“As we grew we would see correlations between some of our reviews running and those artists’ tour dates starting to sell out.”

– Src.

Timeliness – the key to “The Big break”

When Pitchfork posted its review on Radiohead’s album Kid A in 2000, It was one of the first Kid A reviews posted online, and Radiohead fans spread it across the internet, accelerating Pitchfork’s traffic and, in turn, its influence. Also, they introduced annual guides to the year’s best releases which attracted more interest, and so did surveys of prior decades.

That year their readership shot up from 30,000 to 150,000 visits per day.

By the end of 2003, Pitchfork had published around 5500+ reviews from 150+ different authors, with an average length of just over 500+ words.

What’s next for Pitchfork?

An increase in readership means an increase in advertising opportunities and Ryan was able to manage both content (from the network of writers) and ad sales till 2004. It was rather hard to get an advertiser to fill up your ad inventories and you can’t see any programmatic at all.

To put this into perspective, AdSense was just a year old in 2004 and DoubleClick offered DART (Dynamic Advertising Reporting and Targeting), one of the first advertising technology for both publishers and advertisers which reportedly used 26 factors including keywords, domain name, and time to target ads to the online readers (Src). Even if you’re able to get some businesses to advertise through DART, banner blindness and lousy user experience scared most of the publishers and advertisers.

So, you are pretty much tied to direct sales and sponsorships. It was apparent to get a full-time sales rep and Ryan snatched the best from Onion.

Meet, Chris Kaskie

2004

Chris Kaskie (who used to sell the ad space for onion, prior to this) applied for the role in 2004 and got in. The revenue generated in the first four months of his tenure is more than the prior five years combined together.

Pitchfork Music Festivals

2005

The publisher figured out they have millennial readers who would love to attend any sort of music event. In 2005, Pitchfork came up with the “Intonation Music Festival” which was supplemented by Microsoft (Xbox) and others.

The event was a success and attracted around 15,000 music fans. After this trial run, the publisher decided to ramp up the event with a new name ‘Pitchfork Media Festival”.

Thanks to the first Pitchfork Music Festival in 2006 (which gave them massive reach) and increasing ad revenues from the reach. At Berklee’s 20th annual Zafris lecture, Chris revealed that they didn’t make any money off the festivals for three years. But they didn’t lose any too (Src).

Tickets were sold at $15 and 20,000 people attended the first event and interestingly, there’s not even a single advertising excerpt on the Pitchfork website about the event.

Most-popular Independent Music Publication

2006

The festival gave the extraordinary brand reach for Pitchfork and during 2006, the website attracted more than 240,000 readers per day, and more than 1.5 million unique visitors per month, making it the most popular independent-focused music publication online.

You can consider 2006 as the second breakthrough for the publisher after Kid A review.

Pitchfork TV – Pivot to Video

2007

If you think launching a festival is pretty difficult for a media publisher, Pitchfork launched “Pitchfork TV” the very next year.

By 2007, Ryan Schreiber moved to NY to see more concerts and connect with more artists. Pitchfork TV was introduced with shows like ‘Don’t Look Down’, which featured live performances on rooftops.

The important thing to notice here is the pivot of the publisher. As we mentioned above, the publisher never failed to stand out from the crowd by making outlandish moves.

Pitchfork TV made sense to the publisher in many ways.

a. Facebook – Facebook, now the largest social media giant actually started to grow from 2006-2007 and the business pages and advertisements were exploding across the network. The publisher knew how to capitalize on the community.

b. Youtube – Youtube was acquired by Google for $1.65 billion (just a year before) and Youtube had only one purpose – make internet users share and view as many videos as possible. The video was slowly gaining traction and if you have young readers, you can bet most of them will be on Youtube.

c. Google – DoubleClick Merger – DoubleClick had survived the dot-com bubble and strongest presence in the display and video advertising market. Google decided to nab DoubleClick for $3.1 billion to bolster its display and video advertising arm. This, in turn, helped the publisher to see the opportunity on video advertising.

And, it worked.

Once the publisher jumped into video, it bagged big brands like American Express Co, Apple Inc, etc. as sponsors. Eventually, the reviews on the site began to directly compete with other music titles.

For the record, the publisher has grown its presence and garnered millions of views from Youtube every month.

Youtube Stats:

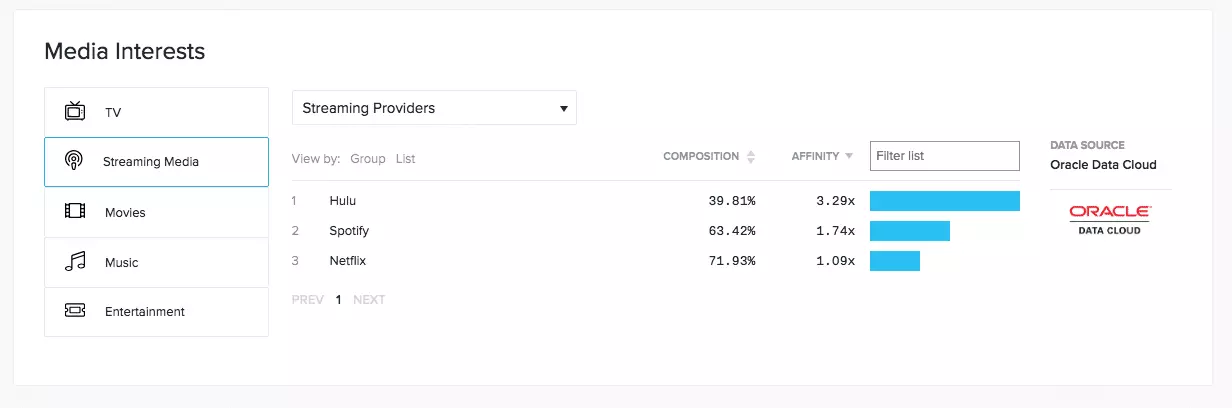

The audience affinity toward streaming services is also high.

Partnerships

2008 – 2010

When you’re a niche publisher, it’s necessary to forge direct partnerships with other companies. Pitchfork knows it well and has been working with several brands for the last decade.

a. Fader Media

Fader Media, one of the emerging music magazines has a lot in common with Pitchfork. Hence, they’ve decided to leverage each other for advertising and reaching a more relevant audience (Src).

During 2008, Fader Media had 1.3 million reach (print and online properties combined) and Pitchfork had around 1.6 million unique users and 16 million page views. So, it made perfect sense for them to sell advertisers a combined audience.

In fact, both the publisher already have some common ad clients like Southern Comfort. As a part of the partnership, both shared content and Ads. However, the editorial team remained intact.

b. Take-Two software

The tie-up with the Fader Media wasn’t surprising. They both are into music and attract a similar audience through different mediums (Fader – Print Magazines, Pitchfork – Online website).

“Partnering with 2K Sports is a natural fit for Pitchfork, as they’re a like-minded company that shares a passion for music and a desire to promote forward-thinking and exciting new projects instead of following a more traditional path. We’re thrilled to work with 2K Sports to select one half of the Major League Baseball 2K8 soundtrack, and can’t wait to play the game.”

– Chris Kaskie, Pitchfork Media.

But, the publisher inked a deal with Take-Two software the same year to curate the In-game sounds and soundtracks of the “Major League Baseball 2K8” game. It turned out well for both parties. Later, they made a deal with a video game magazine “Kill Screen” too.

c. ABC news:

ABC News started a new series dubbed ‘New Music Monday’ and invited Pitchfork to be a part of it. Pitchfork writers regularly appeared on the series debating about the music artists and notable albums. This, in turn, helped the publisher to reach a wider audience and expose themselves across the music landscape.

Death of Music Journalism?

The music publisher was growing and expanding across the globe while everyone was questioning the existence of music journalism.

“Music journalism is dead, long live music journalism.”

– Src.

At first, the partnerships signed by Pitchfork looked weird. But the publisher did what they have to do. They diversified to strengthen their claim of “trusted voice in music”.

Altered Zones

2010

The expansion didn’t stop with the deals and partnerships. The publisher rolled out “Altered Zones” to explore the rising DIY music. Altered Zones, a team of 14 music blogs went live in July 2010.

“The site’s mission is to highlight the most notable and adventurous new artists, and to serve as a focal point for the flood of creativity coming from deep within the music underground.”

– Src.

After a year of running, the publisher shut down the Altered Zones with no clear reasons. Many speculated the impact wasn’t as big as expected and besides, the publisher might have deprioritized the blog over pitchfork.com

The co-editors later came up with Adhoc.fm with the same motto and it is still live attracting thousands of visitors.

Online innovation

2011

The reason why we’ve said that the publisher might have deprioritized Altered Zones over pitchfork.com is due to the revamping process that followed after the closure of Altered Zones.

“Our goal is to be the best music magazine in the world, not the biggest”

– Matt Frampton, Pitchfork’s VP of Sales.

Even after 2010, many music magazines and websites ran with worn-out designs. Some (like The Quietus) focused on content rather than design, while others decided to just run without any redesigns.

Pitchfork saw an opportunity to hit the refresh button. The publisher came up with “Cover stories” to conduct in-depth interviews with the music artists and present it in a way, they never did before.

Especially, the story of Daft Punk has attracted several hundred thousand page views within a week of publishing. The average time on the page was more than six minutes. The publisher was moving away from the page view rat race and launching itself into the heart of the online music industry.

Cover stories remain ad-free for now. But the publisher will likely monetize them soon. As we can’t just run standard display ads or video units, the publisher has been experimenting with new content ad formats that will go well with the stories.

This isn’t the only instance where the publisher went off the track to do something creative. To celebrate its 15th anniversary, for example, the publisher asked readers to vote on their favorite albums from its reviews archive.

Then, it curated an interactive infographic to show the results along with the full-screen creatives (not the standard ad sizes) from Converse. The only problem with the custom ad creatives and content formats are, they require a lot of time and money to scale up.

It’s true that you could charge more for the custom ads, but you need to work closely with an agency to get advertisers and a strong creative team to spit out cool creatives. Pitchfork always included or at least tried to include the custom ads into its monetization strategies.

Note: It’s okay to try it when you’re an established brand or a legacy publisher. Though Pitchfork ran on a tight budget, they have grown their presence over the years and it was enough to experiment with the new formats.

Expand

2013

The publisher launched a weekly print magazine “Pitchfork Review” in 2013, which sells for just under $20.

Why a successful online publication should branch off a print magazine? After all, even the biggest media companies are still struggling with offline circulation. Well, there’s a catch.

Pitchfork relies on its audience to make any decisions. And, considering it never hesitated to experiment, Pitchfork Review isn’t a big shock to the industry. The American Society of Magazine Editors nominated Pitchfork for a National Magazine Award for general excellence in digital media in 2013. It won.

For those who are wondering about the magazine’s influence on revenue, Kaskie shared the fact that the site itself represents 80–85% of the company’s revenue (Src).

In 2013, Pitchfork launched “ October”, a digital publication focused on beer with an editorial perspective that speaks to the beer drinkers. The site was launched in partnership with ZX Ventures, AB InBev’s incubator and venture capital fund that focused on increasing awareness and excitement around beer and brewing culture.

However, not all of the strategies worked well for the publisher. Nothing Major, a site to talk about visual arts failed similarly to its Altered Zones. The publisher continued the expansion nevertheless.

Social Media Strategy

2015

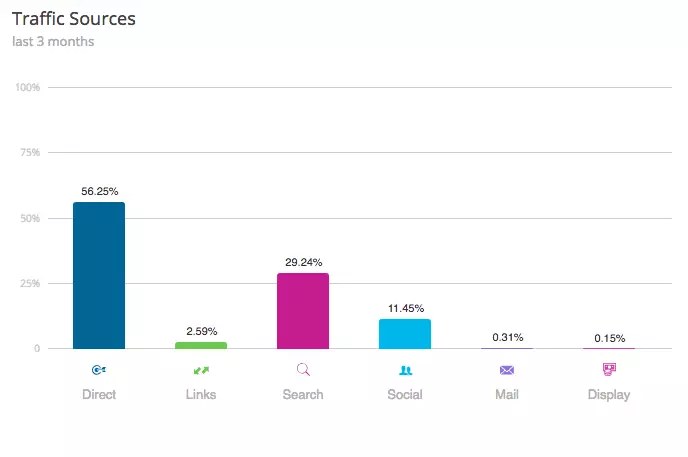

Social Media is still one of the strongest traffic sources for the publisher. As per SimilarWeb, social traffic accounts for 11% of the total traffic to the website.

Buffer interviewed the Director of Social Media at Pitchfork to learn more about the strategy behind the growth.

“We started out with teasers, saw that they were doing well, and evolved our strategy from there. I think using video in social is undeniable at this point. You can’t survive solely on YouTube anymore because if you have the content, you have to go where your viewers are.”

Pitchfork started creating its own video teasers specifically targeting social media platforms. For Facebook, the publisher would try a different video format with different content and for Twitter, the strategy would be completely different.

This isn’t new. We saw the same channel-based approach in our bleacher report episode. So, as a publisher, it’s imperative to work towards a platform-specific strategy to ensure your reach.

New Ventures and M&A

It opened Pitchfork Radio in 2015 and it has attracted a suite of sponsors and advertisers to back it up.

It doesn’t mean that the website has not been on focus. The publisher has grown its user base to 5 million unique visitors a month when it started its radio arm. One thing to notice is the targeting capability of Pitchfork. Despite the exponential growth, the site has managed to attract millennial readers predominantly (Src).

Pitchfork, for the first time, partnered with The Scene, the video-sharing platform headed by the Conde Nast. As you have guessed, the deal was the initiation of the acquisition talks.

The deal went so well that the publishing giant decided to acquire Pitchfork all together. Is it the whole story?

Of course not. By the time Conde Nast bought Pitchfork,

a. Pitchfork.tv crossed 1 million plays.

b. Pitchfork has stabilized its events, festivals, print, and radio arms.

c. It has become more than a website criticizing Indie music.

How about the publisher? Are they willing to merge with the Conde Nast?

You can hear it from the founder himself.

An incredibly proud and exciting day for us at @Pitchfork. We are officially a part of @CondeNast! http://t.co/CTQPxOCLgI

— Ryan Schreiber (@ryanpitchfork) October 13, 2015

“[Pitchfork is] A distinguished digital property that brings a strong editorial voice, an enthusiastic and young audience, a growing video platform and a thriving events business”

– Bob Sauerberg, CEO, Conde Nast.

Foray into Programmatic and Header Bidding

2016

Though it was apparent, Conde Nast said that it has plans to increase the digital revenue of Pitchfork and multiply the number of events. It came up with a new programmatic product “Premium at Scale”, which lets advertisers target audience data and context at the same time.

“I think we foresee the future of programmatic here as being a big part of our business”

– Evan Adlman, Senior VP, Condé Nast Media Group.

In an interview with AdExchanger, Adlman revealed that the company has now enabled header bidding and has been experimenting with private marketplaces.

Pitchfork also collaborated on a special issue with Teen Vogue.

Leveraging First-Party Data

2018

Conde Nast, obviously, has built a DMP named ‘Conde Nast Spire’ which captures various data signals to help advertisers frame lookalike audiences and reach potential customers who aren’t targeted before.

Recently, a tech hardware company learned that its customer base was more likely to be music listeners and readers and so it ran ads on Pitchfork, not Wired.

Conclusion:

Pitchfork isn’t a typical news publisher with a hundred million readers. It’s a niche publisher that ran on a shoestring budget (it changed only after the Conde Nast deal). It has faced criticism, failed at a couple of ventures (Nothing Major, The Dissolve, Altered Zones, etc), and relied on a network of freelancers.

But the publisher didn’t give up. It focused on the proven strategies, experimented with new ad/content formats, leveraged the audience data, and implemented programmatic techniques.

It’s time for you to give up the excuses and start building your media empire.